Why New York Became America’s Entertainment Capital

When we talk about Broadway now, it’s easy to act like New York was always destined to become the center of American entertainment. But “Broadway” wasn’t a natural law. It was an outcome—built by population pressure, immigration, transit, money, and a rapidly evolving commercial culture that learned how to package fun like a product.

By the early 20th century, New York was an audience factory. Between 1900 and 1915, the United States saw more than 15 million immigrants arrive, and by 1910, three-fourths of New York City’s population were immigrants or the children of immigrants. That kind of density doesn’t just change the language on the street; it changes what people will pay to see on a Tuesday night.

Ellis Island is part of this story not as a symbol, but as a pipeline. The scale was staggering—1907 alone was the busiest year in Ellis Island’s history, with more than 1.2 million arrivals, and a single day in April processed over 11,000 people. This matters because entertainment follows crowds, and crowds follow opportunity. New York had both.

A city that could sell you a night out

New York also had something that turns performance into an industry: a thick web of commerce. Publishing, advertising, finance, and retail were already entrenched, and the modern middle class was emerging with leisure time and disposable income. Theatre didn’t stop being elite overnight, but it started to develop a different relationship to the public—more repeatable, more scheduled, more marketed. A show wasn’t just an event. It was inventory.

Broadway became a district before it became a myth

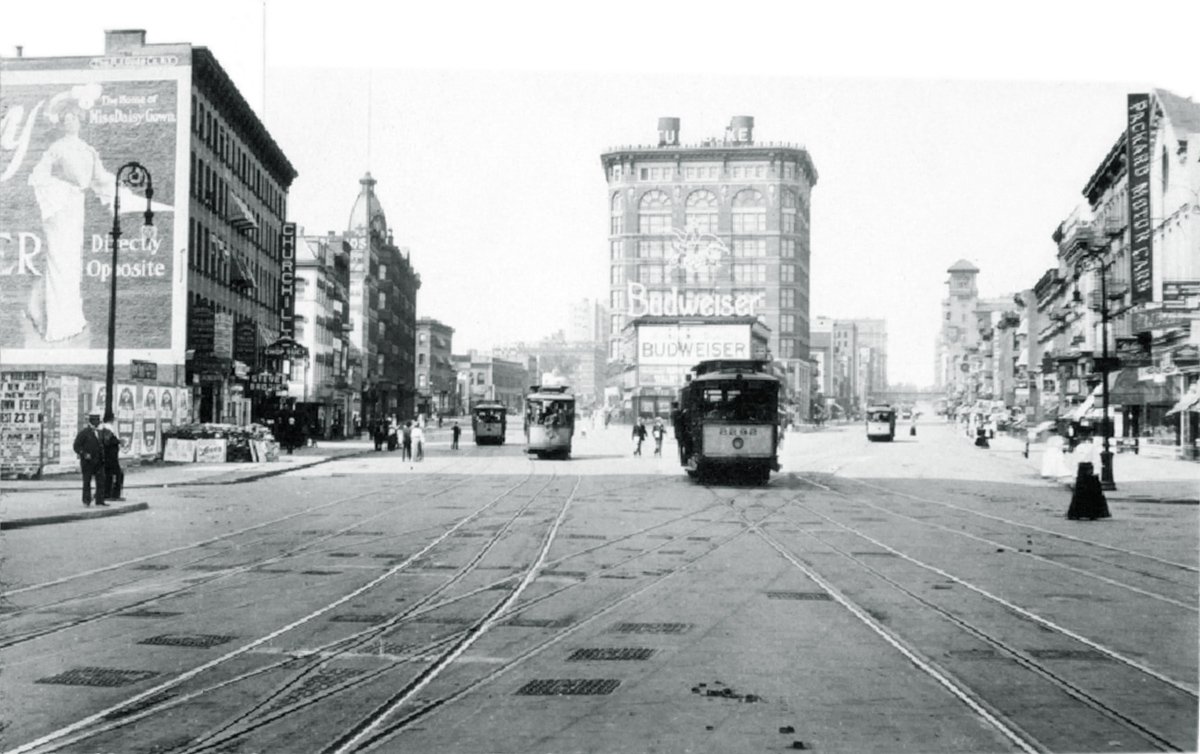

Broadway, the street, gave the whole thing a name, but the real story is the cluster: the Theater District around Times Square and Midtown, where proximity created a feedback loop. Today’s Broadway is still defined by that logic—41 professional theaters, generally 500+ seats, concentrated in the district (with Lincoln Center as a notable extension).

That physical concentration had consequences. Producers could scout talent quickly. Audiences could make choices last-minute. Press could cover multiple openings in the same neighborhood. Theatergoing became a habit because it was convenient, and once it became a habit, the commercial incentives got sharper. Competition raises volume. It also raises the appetite for spectacle, stars, and the kind of storytelling that plays cleanly to a mixed crowd.

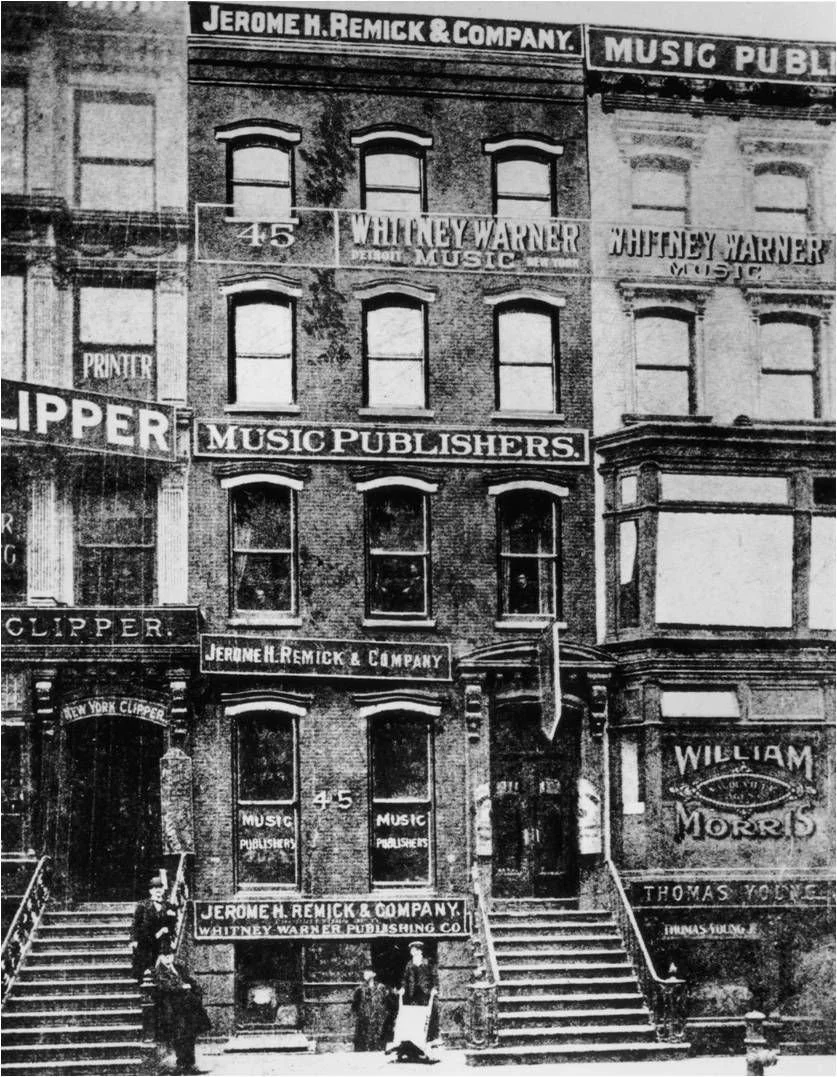

Tin Pan Alley: the songwriting machine in the same city

Just south of that theatrical cluster sat another engine: Tin Pan Alley, the dense corridor of music publishers and songwriters associated especially with West 28th Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenue. This was popular music as manufacturing—songs built to sell sheet music, designed to travel, designed to be repeated.

Musical theatre didn’t emerge in a vacuum; it absorbed that business model. When you can write a hook that people want to take home, you’re not just entertaining them for two hours—you’re extending the life of the show beyond the building.

Variety culture trained performers to last

New York’s entertainment ecosystem didn’t start with “legitimate theatre.” It grew out of variety: vaudeville houses, burlesque, concert rooms, immigrant-language stages, novelty acts, dance halls. What’s important here is not nostalgia—it’s infrastructure. Vaudeville wasn’t just a style; it was a system, with circuits, booking practices, and corporate consolidation (Keith-Albee and Orpheum become key names in how “big-time” vaudeville was controlled and distributed).

This world trained performers who could handle brutal audiences, adapt material quickly, and sustain a professional pace. Broadway benefited from that talent pool and that work ethic, even when it pretended it was a “higher” form.

Centralization creates power—and it also creates gatekeeping

There’s no honest version of this history that skips the exclusions. Centralized entertainment industries don’t just elevate talent; they decide what’s “sellable,” who is “bankable,” and which stories get treated as universal. Black artistry shaped American music and dance profoundly, and New York’s cultural life reflects that—including the Harlem Renaissance’s visibility in the 1920s—yet Broadway’s access points were often restricted even as it drew from the wider culture around it. Business Insider

That tension—between creativity and commerce, between influence and access—is part of what Broadway is, not just what it was.

Why New York, specifically?

Other American cities produced extraordinary entertainment cultures. New Orleans shaped American music. Chicago became a major theatrical and comedic hub. Los Angeles built a screen industry that eventually eclipsed stage in pure scale. But New York had a rare concentration: a massive population, a constant influx of new communities, a dense transit-and-walk culture, and the commercial machinery that could turn art into a repeatable product quickly and publicly.

Broadway didn’t just reflect American culture. It organized it.

And once that organizing principle locked in—district, press, producers, unions, touring pathways—the idea of New York as the place where you “make it” became self-reinforcing. Broadway became both a real neighborhood and a national symbol, and that double identity is exactly why it still holds cultural gravity now.