Inventing Broadway While Being Shut Out of It

Broadway loves a comeback story. It loves to tell us that talent rises, barriers fall, and the stage slowly becomes “more inclusive” over time.

But the early Black history of Broadway doesn’t fit neatly into that narrative, because the system wasn’t accidentally racist. It was built that way. Which means “progress” can’t just be measured by who gets applause. The real question is whether success inside the system changes anything about the system itself.

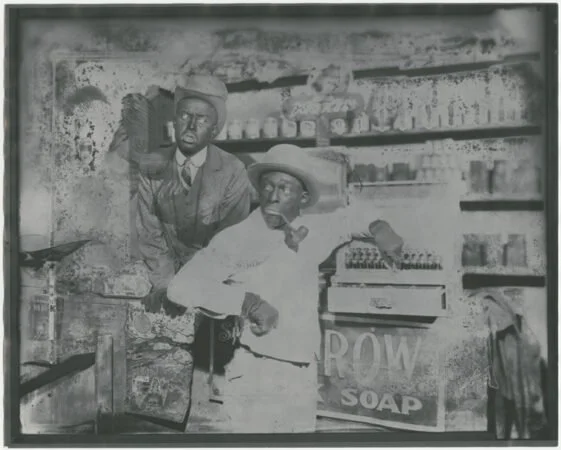

Take Bert Williams. Ziegfeld protected him because he was undeniable—“I can replace everyone except Bert Williams.” That’s a kind of victory. Williams became a Broadway headliner, a star whose emotional precision expanded what comedy could do. And yet he performed in blackface and was still treated as second-class offstage: barred from hotels, restaurants, basic dignity. If that’s progress, it’s brutal progress. Williams had agency in his craft—timing, pathos, the quiet intelligence underneath the laugh—but very little agency in the terms of his visibility. The producer and the audience shaped what “sold,” and the performer paid the cost.

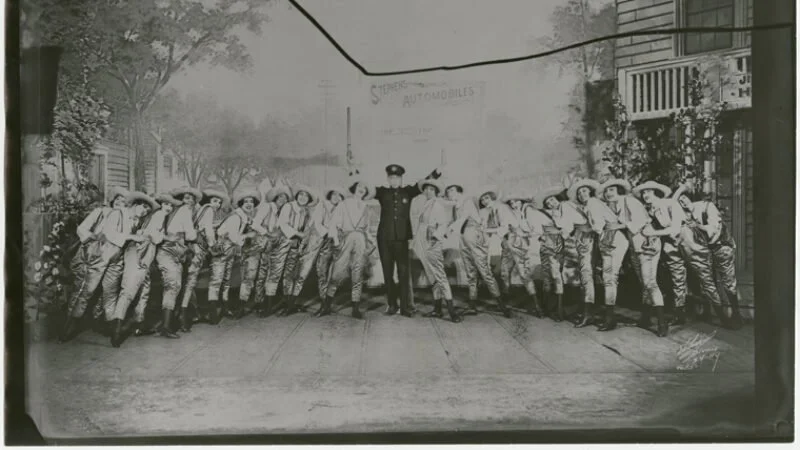

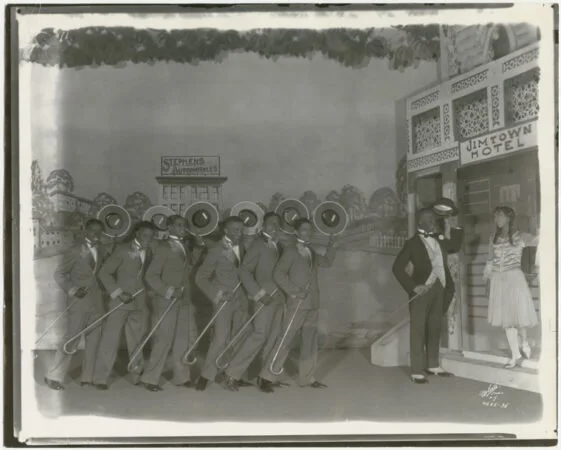

Now look at Shuffle Along (1921). The transcript makes it clear: the characters didn’t stray far from minstrel stereotypes. That’s not a footnote; it’s the contradiction at the center of the show. And still—this same musical cracked open Broadway’s imagination. A hit written and performed by Black artists. A massive, mixed-race audience with unsegregated seating. Midnight performances because white Broadway casts couldn’t stop talking about it. A pipeline of talent: Florence Mills, Josephine Baker, Paul Robeson. A run so successful it proved what the industry pretended not to believe—that audiences would pay to see Black artists onstage in Black-authored work.

So is that “success on the system’s terms”? Partly. Shuffle Along used familiar types to get a white producer to take the risk. It played a game that was rigged.

But it also changed the board. It shifted demand. It created jobs. It built a new appetite for Black shows that led to dozens more musicals in the decade that followed. It helped ignite the Harlem Renaissance—not because the show was politically pure, but because it made space for Black artistry to be seen, hired, and imitated in the commercial center of American entertainment.

That’s the both/and we have to hold.

Working in stereotype to “get in the door” can be a form of strategy, and it can also reinforce harm. The same act can do both at once. The system rewards the mask, then punishes you for wearing it.

So what does progress look like when the foundation is rotten?

It looks like Bob Cole writing a declaration of independence demanding control—Black stage managers, Black orchestra leaders, Black audiences seated from the front row back. It looks like Abbie Mitchell’s classical training moving between theatre and concert stages, refusing to be reduced to one sound, one role, one expectation. It looks like Shuffle Along proving a market existed, even when the market was shaped by racist appetites.

Progress isn’t just applause. It’s leverage. It’s access. It’s infrastructure. It’s the slow, stubborn work of forcing a system to widen—until the door that was cracked open can’t be shut again.