The 10 Shows That Pushed Musical Theatre Toward the Integrated Musical

The 10 Shows That Pushed Musical Theatre Toward the Integrated Musical

(Before Oklahoma!) The integrated musical did not suddenly appear in 1943. By the time Oklahoma! opened, Broadway had already spent decades experimenting with how music, story, character, and theme might function together rather than separately. These ten shows—presented in chronological order—represent key steps in that evolution.

Show Boat (1927)Show Boat challenged the notion that musicals had to avoid serious subject matter, confronting race, addiction, and fractured families. Its songs grow directly out of character circumstance, establishing a new expectation that music could deepen narrative rather than distract from it. Integration here was imperfect, but the ambition was unmistakable.

Of Thee I Sing (1931) This political satire made history as the first musical to win the Pulitzer Prize. Songs function as commentary and critique, advancing ideas rather than spectacle. It proved that a musical could be intellectually cohesive, not just entertaining.

Strike Me Pink (1933) Surreal, openly camp, and politically absurd, Strike Me Pink pushed tone and style as organizing forces. While its narrative is loose, the show demonstrated that unity of voice and attitude could matter as much as plot mechanics. It expanded what “cohesion” could look like onstage.

Anything Goes (1934) Cole Porter’s musical comedy refined wit, sexuality, and sophistication into a tightly controlled world. Though not fully integrated, its consistency of tone aligned music, lyrics, and character in ways earlier shows had not. It showed how musical identity itself could unify a piece.

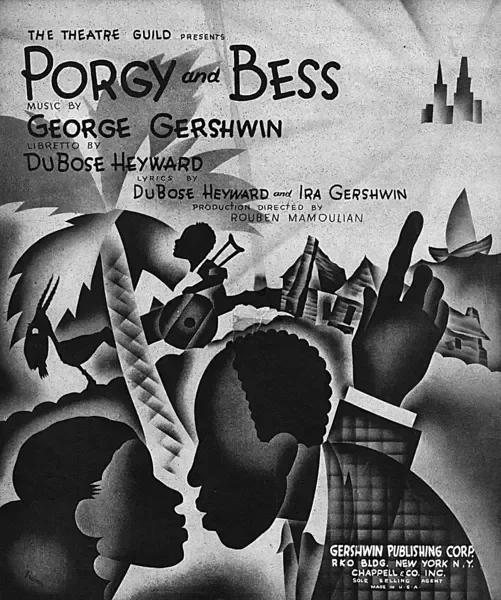

Porgy and Bess (1935) Blending opera and musical theatre, Porgy and Bess aimed for total synthesis of music, story, and community. Gershwin envisioned a work where song was inseparable from dramatic structure. Its cultural legacy is complex, but its ambition reshaped expectations for scale and seriousness.

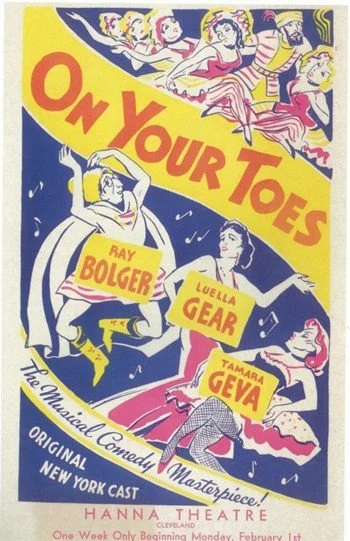

On Your Toes (1936) This Rodgers & Hart collaboration integrated ballet directly into narrative storytelling. Dance was no longer decorative—it carried plot and character meaning. The show expanded integration beyond song into movement itself.

Babes in Arms (1937) Centered on young artists creating theatre as an act of survival, Babes in Arms blurred the line between story and performance. Songs arise from necessity and purpose, not convenience. The show reinforced the idea that motivation could anchor musical structure.

The Cradle Will Rock (1937) Marc Blitzstein’s labor musical fused politics, music, and narrative into a single ideological statement. Famously censored, its form became part of its meaning. Integration here was radical: music and message were inseparable.

Pal Joey (1940) With its unapologetic antihero, Pal Joey rejected sentimental resolution. Songs expose character flaws rather than redeem them, pushing psychological realism forward. Integration became about emotional honesty, not moral comfort.

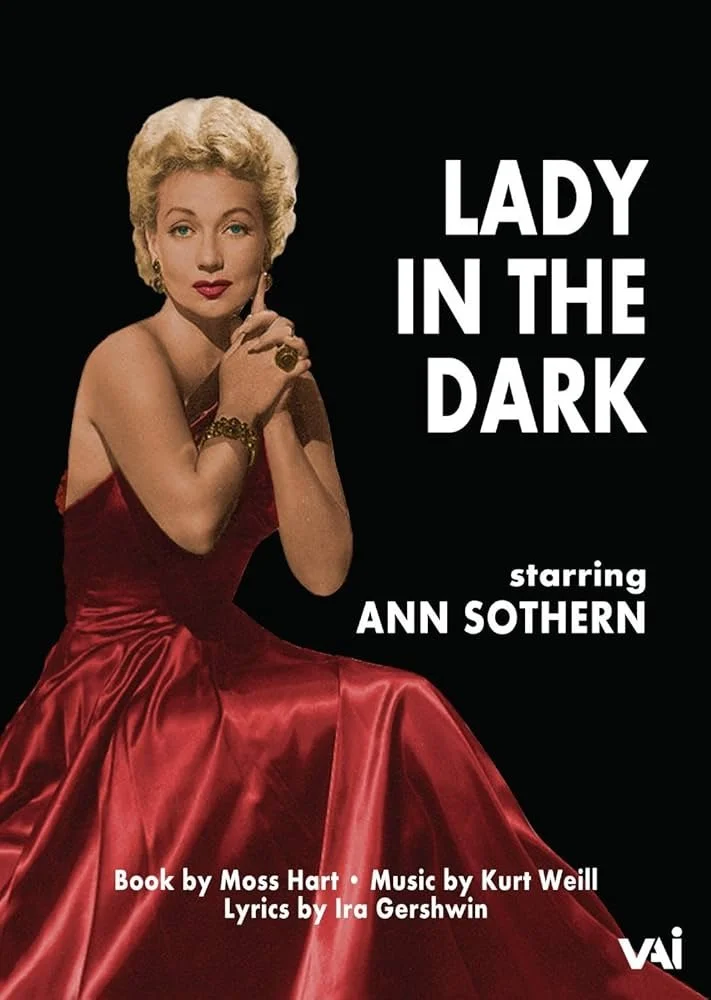

Lady in the Dark (1941) Set inside a woman’s psyche, the musical places all songs within dream sequences. Music exists only where language fails, redefining when and why characters sing. It expanded integration into psychological space.

By 1943, Broadway had already tested integration through politics, psychology, dance, satire, and social realism. Oklahoma! did not invent the integrated musical—it clarified, streamlined, and popularized a form that was already being built.